In September, a new school year will begin, bringing back textbooks, school supplies, and a packed schedule of exams – including matriculation exams for older students. These are formative years in which our children grow and develop, years that can significantly impact their academic and professional futures.

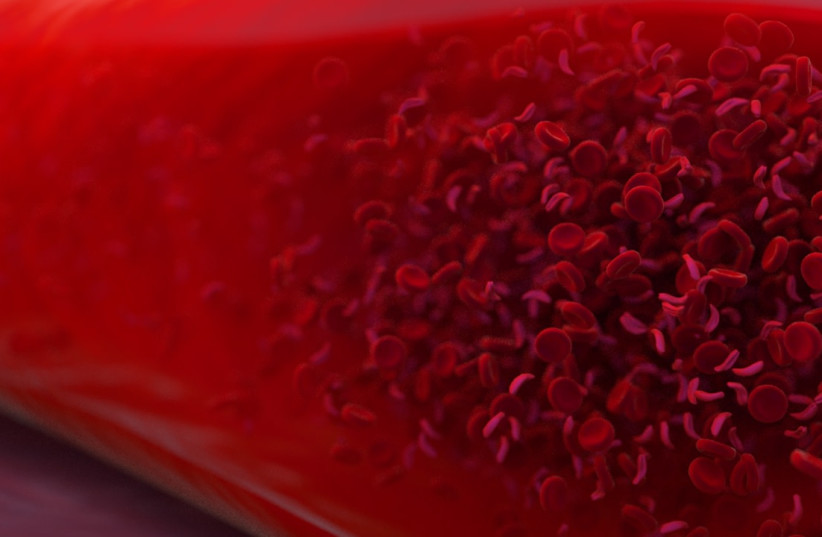

Alongside the usual educational routine, there is a crucial issue that especially affects adolescent girls and can directly influence their academic achievements: iron deficiency.

As the new school year approaches, we must ask ourselves not only which school track they’ll choose or which major they’ll pursue, but also, is their body prepared for learning?

Iron deficiency and anemia in teenage girls are not a new phenomenon, but it has recently gained concerning attention following the publication of a new position paper by the Israel Medical Association.

Research on iron deficiency and anemia in adolescent girls

The document unequivocally states: iron deficiency and anemia among adolescent girls in Israel are common, and they have a direct impact on cognitive ability, mental health, concentration, physical functioning, and academic performance. These effects can occur even before clinical anemia develops.

Half of teen girls have iron deficiency and a third have anemia, yet few are diagnosed.

According to the position paper, up to 50% of teenage girls suffer from iron deficiency, and around 30% are diagnosed with anemia. The most recent national nutrition survey (2014-2016) found that 17.5% of girls aged 12-18 reported a past diagnosis of iron-deficiency anemia, compared to just 7.4% of boys.

These numbers likely reflect significant underreporting, as they include only those who were officially diagnosed. According to Magen David Adom, 26% of female soldiers who volunteer to donate blood are disqualified due to low hemoglobin levels.

Iron deficiency during adolescence is caused by several overlapping factors. First, physiological changes – this stage of life is marked by rapid growth and physical development that require increased iron intake. Second, the onset of menstruation – monthly bleeding, often heavy, results in a consistent loss of iron. Third, dietary habits – vegetarianism, veganism, dieting, irregular eating, or food insecurity all impair daily iron intake.

The main message of the position paper is revolutionary: iron deficiency is a health issue in and of itself – even when anemia has not yet developed. A drop in ferritin levels (a measure of iron stores in the body) can manifest as chronic fatigue, weakness, reduced attention and concentration, poor academic performance, and decreased quality of life without abnormal hemoglobin values in routine blood tests. Early detection is only possible by measuring ferritin levels, which allows identification of deficiency at its earliest stage.

The responsibility to address the issue

The responsibility lies with all of us: doctors, schools, parents, and the girls themselves.

The impact of iron deficiency on adolescent girls is a critical and necessary conversation that affects their quality of life, academic achievements, and even their future as healthy women and mothers.

This is a shared responsibility – of family physicians, pediatricians, gynecologists, educators, parents, and the girls themselves. Creating open, informed discussions about the importance of iron, routine screening, and a rich nutritional intake are steps that can drastically reduce the number of girls suffering from iron deficiency and anemia.

Stakeholder involvement should lead to a multi-faceted approach: routine blood tests for all girls at ages 15–16, including a full blood count and ferritin levels; proactive conversations with teens about nutrition and menstruation (e.g., cycle duration and bleeding intensity); professional guidance on iron-rich foods (such as red meat, fish, legumes, and spinach); and iron supplementation when necessary, followed by proper monitoring.

Schools must be active partners, not passive observers. Schools play a central role in the educational and social development of girls, but their responsibility doesn’t end with academics. When it comes to student health, especially nutrition and well-being, schools must act as proactive partners.

This is not only a moral duty, but also a clear educational interest. Girls suffering from fatigue, poor concentration, or decreased functioning cannot realize their full potential in the classroom.

Schools should integrate age-appropriate health education into the curriculum, where topics like nutrition, body image, and menstruation are discussed openly, including deeper questions such as cycle length, bleeding volume, and the critical role of minerals like iron.

Workshops, seminars, and integration of relevant content into science and health classes can equip students with the tools to recognize early symptoms like abnormal fatigue or a sudden drop in energy – in a clear and accessible way.

During middle school, when hormonal changes begin, it’s especially important to foster open, approachable conversations between students and school counselors, nurses, and teaching staff. One way to raise awareness and encourage early screening is through partnerships between schools and healthcare providers.

Joint initiatives with medical professionals – such as educational content and onsite blood tests – can offer meaningful, accessible health value, and help remove hidden biological barriers that prevent girls from reaching their potential.

Now is the time to do screenings

Why now? Because it’s an investment that will pay off in health and academic success.

The position paper clearly states that early detection of iron deficiency meets all the World Health Organization’s criteria for a public screening program. This is a common condition, easily identifiable, and treatable with low-cost, effective interventions. The cost of a blood test and iron supplement is far lower than the social and economic costs of academic failure and long-term health damage.

Now, ahead of the new school year, we have a valuable opportunity to pause and consider how we can create a better future for girls in Israel. It’s time to look beyond class schedules – and ensure that physical health is in place to support learning.

In addition to its impact on current well-being and cognitive ability, prolonged iron deficiency during adolescence can affect future fertility.

At an age when the body is building iron reserves necessary for a healthy pregnancy later in life, an untreated deficiency may have lasting consequences. The girls of today are the women of tomorrow – and their health cannot wait.

The more we simplify the message, eliminate stigma around menstruation and nutrition, and link everyday symptoms with real nutritional deficiencies, the more girls we can help avoid delayed diagnoses and improper treatment.

Health education is not a luxury; it’s a fundamental condition for growth.

The writer is scientific director at Altman Health.