Simchat Torah celebrates the role of the Torah in Jewish history. This holiday is not mandated by the Torah itself but emerged through Jewish custom over time.

The practice of completing the Torah reading cycle on the second day of Shmini Atzeret, as observed in the Diaspora, dates back at least 2,000 years to the Talmudic era.

Because this day marked the conclusion of the Torah, it became a celebration in its own right. The earliest records of a distinct Simchat Torah celebration appear about 1,000 years ago. Jewish custom elevated the second day of Shmini Atzeret into a separate holiday, with its own theme and spirit.

The final section of the Torah, read on Simchat Torah, describes Moshe’s death. As Moshe prepares to depart, he turns to his people and delivers blessings. In this moment, he echoes Jacob, who had gathered his children to bless them before passing away.

After 40 tumultuous years of leading the people through the desert, with its highs of triumph and lows of failure, Moshe brings his leadership to a close with a heartfelt blessing for the nation he guided. As he begins his blessings, Moshe evokes the revelation at Sinai, recalling the moment when the Torah was given.

Torah as fire and heritage

While recalling that day, Moshe constructs two seemingly opposite images. First, he portrays the Torah as descending with divine fire: “from His right hand, a fiery law for them.” This image suggests a Torah that is heavenly, absolute, and untouched by human experience. The divine fire signaled it was the word of God, unaffected by human choices or historical change.

Yet, in the same breath, he describes the Torah as the inheritance and legacy of the Jewish people: “Moshe commanded us the Torah, an inheritance for the people of Jacob.” Here, the Torah is framed not as distant fire but as national heritage, shaped by Jewish history and lived through Jewish experience. Before he delivers blessings to different sectors of the population, Moshe frames Torah as both heaven’s fire and the lived story of a nation.

Throughout history, Torah has at times stood as a divine, untouchable document; and at other times, it has been woven into the currents of history, carried and shaped by the Jewish people.

Torah woven into society

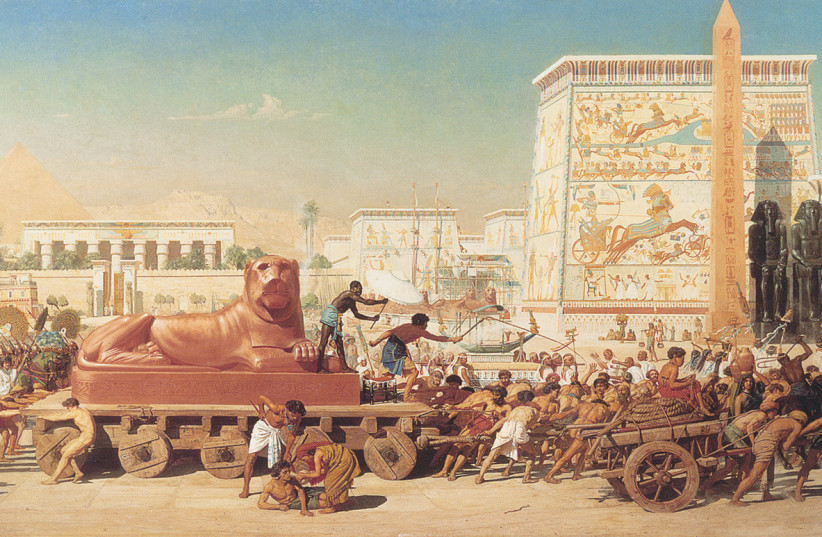

During the great 1,300-year golden age of Jewish sovereignty, Torah was deeply woven into the fabric of society. We were governed as a theocracy, and Torah law guided judicial decisions and social practice. Many commandments are communal in nature, requiring a sovereign Jewish polity rooted in the Land of Israel.

In that context, Torah and daily life were inseparable; its commandments were enacted, its values lived, and its authority reinforced by the framework of the state and organization of society. In that era, Torah and Jewish history moved in harmony: We had the land, we had sovereignty, and Torah scholarship flourished.

Torah independent of history

About 2,000 years ago, Torah underwent a profound shift. We were expelled from the Land of Israel. We lost monarchy, sovereignty, land, and much of our cultural framework. The anchors that had tied Torah to lived Jewish experience were gone.

Fortunately, Torah study and Jewish law practice endured. At that point, Torah became a largely self-sufficient world of Jewish experience, able to exist independently of political sovereignty. As the Talmud in Berachot states, from the day the Temple was destroyed, God had only the four cubits of Jewish law and Torah study on which to focus.

This declaration underscores Torah’s ability to flourish even when severed from other elements of Jewish culture or national inheritance.

At this juncture, Torah came to resemble divine fire – elevated, independent, and largely untouched. It stood apart from historical circumstance.

Independent and unquenchable

Not only has Torah at times existed apart from the Jewish experience, but it has also operated autonomously from general history. Several attempts were made to eradicate it, but each effort ultimately failed. Whenever efforts were made to suppress Torah, it often grew in surprising ways.

The Greeks sought to eliminate Torah study, but their defeat sparked one of the greatest Torah supernovas in history: the emergence of the period of the Tana’im. They articulated the teachings of the Oral Torah, which were ultimately compiled and codified into the Mishna in the 3rd century CE.

A few hundred years after Hanukkah, the Romans issued harsh decrees against Torah study and rabbinic ordination. However, these efforts failed and provoked Torah to grow in response. In the immediate aftermath of this persecution, a second generation of Talmudic scholars – the Amora’im – emerged to undertake the monumental task of codifying the Talmudic discussions, not merely the concise statements of the Mishna.

Torah existed apart from human history, and attempts to quench its fire only fanned its expansion.

At the end of the 11th and 12th centuries, the Crusaders swept through Jewish communities of the Rhineland, terrorizing cities in France and murdering numerous Torah scholars. However, in the two centuries that followed, France became a flourishing center of Torah study. The academies of the Tosafot articulated a crucial methodology for Talmudic analysis.

Similarly, the waves of hatred directed against our people in Central Europe during the17th through 19th centuries did not deter Torah’s growth in Central Europe and Western Russia. Torah continued to burn as a divine fire. Not only was it independent of history, but it often thrived precisely when history sought to extinguish it.

At different points in history, Torah has been intertwined with the heritage of the Jewish people, coupled with other elements of communal inheritance. At other times, it has stood apart as a divine fire, untouched by human hands – Jewish or otherwise.

Divided visions of Torah

Now that we have returned to Israel, this question has resurfaced: Should Torah exist apart from society or be fully integrated within it? In the Temple era, every Jew was observant, and all were committed to Torah. It was natural that Torah should be woven into the fabric of a sovereign society and state. In that historical context, the alignment between Torah and social structure was evident.

As we currently live in a sovereign state that is not formally religious, this question takes on new urgency.

Many feel that Torah should once again be the inheritance of all of Israel and fully integrated into society. This perspective shapes everything – from army service to efforts to expand Torah study among Jews who are not observant. It also includes a broader concern of infusing Torah life into every sector of Israeli society, including those with no intention of becoming religious.

This vision sees Torah as the inheritance of the entire people of Israel.

A different approach still emphasizes the image of Torah as heavenly fire. Until broader society becomes classically observant of Torah law, Torah must remain on a separate track, protected and autonomous. Not only should it remain autonomous of broader social interaction, but it also serves as a protest and a shield against cultural pressures. It should not be fully absorbed into a non-observant society; rather, it serves as a hedge, safeguarding against the influences of that society while preserving its spiritual integrity.

In modern Israel, views of Torah diverge sharply. Some see it fully integrated into society; others insist it must remain independent and protected. Some experience it as a heavenly fire, while others see it as a shared national heritage for all to engage at different levels.

The writer, a rabbi at the hesder Yeshiva Har Etzion/Gush, was ordained by Yeshiva University and has an MA in English literature. His books include To Be Holy but Human: Reflections Upon My Rebbe, Rabbi Yehuda Amital, available at mtaraginbooks.com.